Beyond the UI Kit: Why Your Design System Needs Stronger Governance.

Imagine this: my product teams are shipping new features faster than ever. We’re using a brand-new “design system,” and our designers are happy with a full Figma library. Our developers have a matching set of UI tools. Things look consistent, and everyone’s excited. But six months later, problems appear. New, unofficial components are popping up. Different teams are solving the same problems in slightly different ways. The idea of a “single source of truth” now seems like a distant dream. What happened?

It’s likely we fell for the Component Fallacy. This is the common mistake of thinking that a good-looking UI kit is a complete design system. A component library is important, but it’s just one part of a bigger picture. Without strong design system governance—the clear rules and processes for creating, managing, and updating the system—even the best library will fall apart as our company grows and products change.

In this article, I’ll share my perspective as someone who’s been deeply involved with design systems. I’ll look closely at the Component Fallacy and other common governance problems that cause design systems to fail. I’ll also share real-world advice on setting up clear ways to make decisions and practical methods for contributions. By the end, you’ll know how to build a strong design system that not only speeds up work but also helps teams work together better and keeps the system healthy for the long run.

Context & Importance

I’ve found design systems to be incredibly appealing. In a time when getting products to market quickly and giving users a smooth experience are key, I’ve seen companies invest heavily in them. We all hope to work more efficiently and create more consistent products. From my experience, good design systems can even lead to big cost savings and faster product launches. However, I’ve noticed there’s often a big gap between having a design system and succeeding with one. In my work, this gap usually comes down to governance.

I’ve observed the “Component Fallacy” as a widespread issue, especially when organizations push for fast results. I’ve seen teams pour time and resources into creating beautiful UI components in design tools, and sometimes even the corresponding code, only to declare victory prematurely. What gets overlooked, in my experience, is the critical background work: establishing clear processes for updates, creating ways for cross-functional teams to collaborate, ensuring designs integrate smoothly with engineering beyond just the surface level, and defining clear ownership for decisions. When these elements are missing, I’ve watched systems quickly become outdated, lose the trust of teams, or get bypassed entirely. The result, as I’m sure you’ve seen, is design debt—a tangled web of inconsistencies and unofficial components that’s painful to untangle.

Why is this more important now than ever?

- Rapid Scaling: As companies grow, their products and teams also grow. Without governance, this growth leads to mess and fragmentation, not unity.

- Distributed Teams: Many people now work remotely or in different locations. Clear, written governance is vital for teams to work together effectively when they’re not in the same office.

- Tooling Advancements: Tools like Figma and Storybook are great for making and sharing components, but they don’t provide governance on their own. In fact, how easy it is to create new component versions can make things worse if there’s no plan to manage them.

- Increased Expectations: Users expect a smooth, consistent experience everywhere they interact with a product. A poorly governed design system can’t deliver this, leading to a confusing user journey.

Weak governance isn’t just a small problem; it directly threatens the value of your design system investment. Surveys and industry reports show that “poor documentation,” “unclear information about what’s old or broken,” and “no clear way to contribute” are top complaints from design system users. These are all signs of poor governance. On the other hand, successful design systems are much more likely to have clear, effective ways for people to contribute and make decisions.

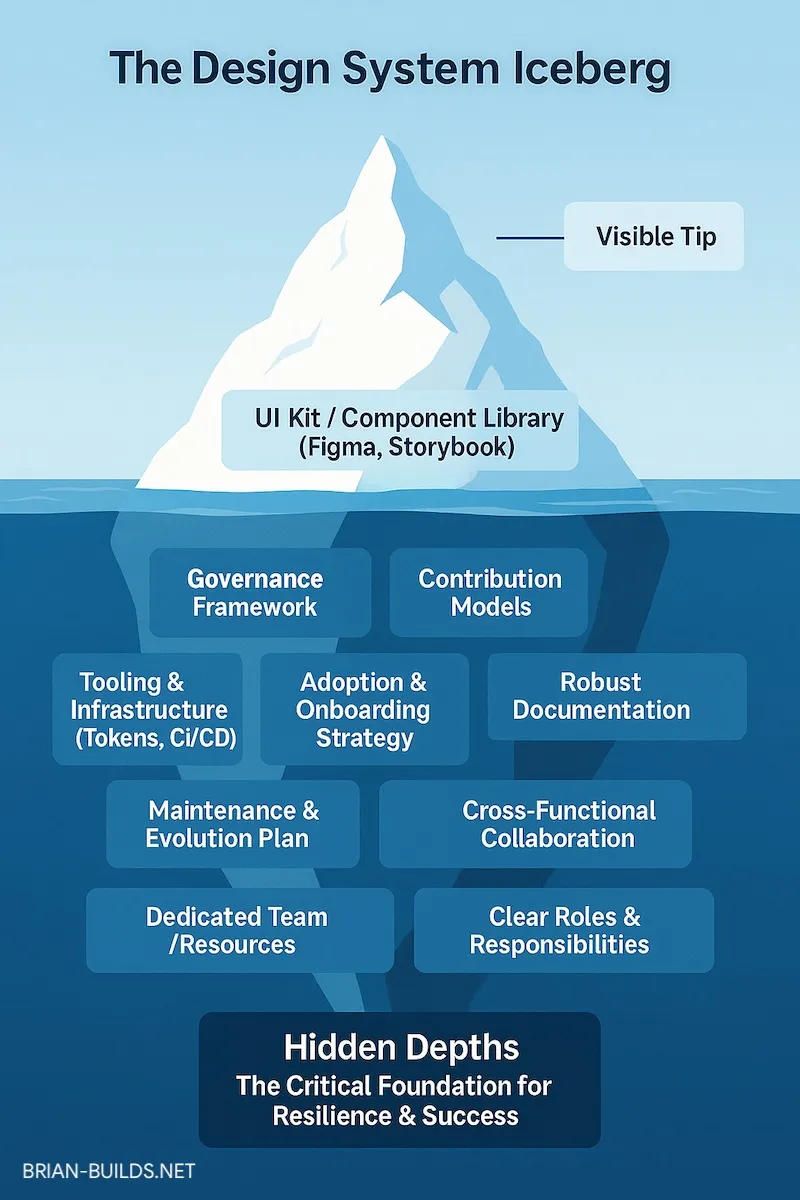

Visualizing the Problem: The Iceberg of Design System Success

To understand the Component Fallacy and why governance is so important, think of an iceberg:

Diagram Description: The Design System Iceberg

- Above the Water (Visible Tip): This is the UI Kit / Component Library (like your Figma files or Storybook). It’s the part everyone sees and often mistakes for the whole design system. It seems like the “easy” part.

- Below the Water (Hidden Depths - The Critical Foundation): This huge, unseen part includes everything that actually makes a design system strong and successful. These are things like:

- Governance Framework: The main rules and processes.

- Contribution Models: How new things are added or updated.

- Decision-Making Structures: Who approves changes and how.

- Robust Documentation: Clear, updated guides.

- Tooling & Infrastructure: Design tokens, automated processes, version control.

- Adoption & Onboarding Strategy: How people learn to use the system.

- Maintenance & Evolution Plan: How the system stays up-to-date.

- Cross-Functional Collaboration: How design, development, and product teams work together.

- Dedicated Team/Resources: The people who take care of the system.

- Clear Roles & Responsibilities: Who does what.

- Feedback Loops & Communication: How the system improves and keeps everyone informed.

This picture shows that the Component Fallacy happens when companies only focus on the tip of the iceberg. They ignore the essential governance and operational parts underneath, which are vital for long-term success and strength.

Key Concepts & Definitions

Before we dive deeper, let me define some key terms that I’ll be using throughout this article.

-

Design System Governance: In my experience, this is the complete set of roles, responsibilities, rules, standards, and decision-making processes that guide how a design system is built, maintained, evolved, and used across an organization. I’ve found that good governance is absolutely essential for keeping the system consistent, reliable, and scalable.

- Example from my work: I’ve seen successful governance plans include a “Design System Council” with representatives from different teams meeting bi-weekly to review and approve new component proposals submitted through a standardized online form.

-

The Component Fallacy: I’ve come to define this as the mistaken belief that a UI kit in a design tool (like a Figma library), or even a matching library of coded components, constitutes a complete design system. In my work, I’ve seen how this view dangerously overlooks the critical processes, engineering integration points, comprehensive documentation, and collaborative workflows—essentially, the governance—that make a design system truly effective and widely adopted.

- Example: A team launches a beautiful Figma library with over 100 components. But they have no clear process for updating them, no specific people in charge of maintaining them, and no clear instructions for how developers should use them. Six months later, the library is out of date, and different product teams have created their own versions of components.

-

Contribution Models: In my practice, I’ve developed these as the structured approaches that enable individuals or teams to propose, create, review, and integrate new patterns, components, or updates into the existing design system.

- Example: A “Federated Contribution Model” might let product designers create a new component within their team. Then, they submit it with details and reasons for needing it to a central design system team. That team then reviews, refines, and adds it to the main library.

-

Decision-Making Structures: Through my experience, I’ve learned that these are the formal and informal mechanisms by which changes to the design system are proposed, discussed, evaluated, approved, and implemented. I’ve worked with various structures—from dedicated core teams to design councils to open community discussions—and I can’t stress enough how critical it is to have clear decision-making processes in place.

- Example: A “Core Team Model” might give a dedicated design system team the power to make final decisions on all changes to the system. This ensures tight consistency but could slow things down if not managed well.

-

Design Debt (in Design Systems): In my career, I’ve seen how design debt accumulates when teams opt for quick fixes rather than well-considered solutions. In design systems, this manifests as design inconsistencies, deviations from established patterns, outdated or unofficial components, and disorganized documentation. I’ve learned that this is frequently a telltale sign of inadequate governance or poor adoption.

- Example: To meet a tight deadline, a team changes a standard button component directly in their product’s code instead of suggesting a new version to the design system. This creates design debt because that button is now different and won’t get updates from the main system.

-

Single Source of Truth (SSOT): In my work with design systems, I’ve come to view the SSOT as the single, authoritative repository for all design and code elements, patterns, guidelines, and documentation across a company’s products. I’ve found that maintaining this reliability absolutely requires robust governance practices.

- Example: If a designer needs to know the correct spacing for a card component, they look it up on the design system’s official documentation website. This website is the SSOT, not an old Figma file or an existing product screen.

Tactical Deep-Dive: Building a Resilient Governance Framework

Avoiding the Component Fallacy and other problems needs a careful, practical plan for setting up governance. It’s not about creating annoying rules; it’s about making things clear, predictable, and understood by everyone.

Step 1: Confronting and Overcoming the Component Fallacy

Through my work with various organizations, I’ve developed a straightforward way to identify if you’re stuck in the Component Fallacy. I recommend asking your team these key questions:

- Beyond our Figma or UI library, do we have documented procedures for how new components are requested, designed, developed, and released?

- Who is specifically responsible for maintaining and evolving our system? Are these roles clearly defined and do these individuals have dedicated time for this work?

- What processes do we have in place to ensure our design files and code components remain in sync?

- How comprehensive and up-to-date is our documentation, and is it easily accessible to everyone who needs it?

- What’s our decision-making framework for system changes and updates?

If these questions reveal uncertainty or gaps, you’re likely experiencing the Component Fallacy. Here’s how I’ve helped teams overcome this:

- Educate Stakeholders: I’ve found it crucial to help everyone understand that a design system is an evolving product that requires ongoing investment. I often use the iceberg visualization to illustrate how much lies beneath the surface of the visible components.

- Conduct a System Audit: I recommend performing a thorough assessment to identify governance gaps and user pain points. This audit becomes the foundation for your improvement plan.

- Secure Necessary Resources: In my experience, you’ll need to make a compelling case for dedicated resources—whether that means full-time staff or protected time for team members to focus on governance.

Step 2: Choosing the Right Governance Model

Having worked with organizations of all sizes, I can confidently say there’s no one-size-fits-all governance model. The optimal approach depends on your company’s unique context. I typically recommend considering three primary models:

-

Centralized Model:

- Description: In this model, I’ve seen a dedicated core team serve as both creators and gatekeepers of the design system. They maintain full control over all additions and changes.

- Pros: From my experience, this model delivers exceptional consistency and clear ownership. The centralized control often results in high-quality output and can accelerate decision-making within the core team.

- Cons: However, I’ve observed that this model can create bottlenecks if the core team becomes overwhelmed. There’s also a risk of becoming disconnected from the day-to-day needs of product teams, potentially leading to resistance from teams who feel excluded from the process.

- Best For: In my practice, I’ve found this works best for new design systems, smaller organizations, or situations where maintaining absolute consistency is the highest priority.

-

Federated Model (Distributed):

- Description: In this approach I’ve implemented, contributions come from across product teams and disciplines. While a small central group provides guidance, the actual work is distributed throughout the organization.

- Pros: I’ve seen this model foster incredible innovation and adaptability. By incorporating diverse perspectives, the system often becomes more robust and relevant to actual product needs. It also builds strong organizational buy-in and shared ownership.

- Cons: The challenge I’ve encountered is maintaining consistency without strong coordination. Decision-making can become protracted if not carefully managed, and there’s a risk of duplicative or conflicting contributions without clear guidelines.

- Best For: From my experience, this works best for mature design systems in larger organizations with multiple skilled product teams who have the capacity to contribute meaningfully.

-

Hybrid Model:

- Description: In my consulting work, I often recommend this balanced approach. It establishes a central team responsible for maintenance and documentation, while a cross-functional committee provides strategic direction and gathers input from across the organization.

- Pros: I’ve found this model offers the best of both worlds when implemented well. It maintains consistency through central oversight while benefiting from diverse input. The system remains adaptable to changing needs while preserving coherence.

- Cons: The main challenge I’ve observed is the complexity of managing this balance. It requires exceptionally clear role definitions and robust communication channels to prevent confusion or duplication of effort.

- Best For: In my experience, this model is particularly effective for growing companies that need to maintain quality while scaling their design system across multiple teams and products.

Practical Advice from My Experience: When helping organizations select a governance model, I always start by assessing their company culture. I’ve learned that a model that conflicts with the organization’s values is doomed to fail. For startups, I typically recommend beginning with a more centralized approach and gradually evolving toward a hybrid model as the company grows. The key insight I’ve gained is that no model is set in stone—I encourage teams to remain flexible and adjust their approach as their needs change. The most important factor is clarity: whatever model you choose, document it thoroughly, communicate it clearly, and ensure everyone understands their role within it.

Step 3: Establishing Clear Decision-Making Structures

In my consulting work, I’ve consistently found that unclear decision-making is one of the primary reasons governance initiatives fail. I’ve seen too many promising design systems stall or collapse under the weight of decision paralysis or, conversely, from autocratic decision-making that alienates key stakeholders.

Structures I’ve Found Effective:

- Core Team: I’ve worked with organizations where a dedicated design system team makes most decisions. While this approach can be efficient, I always caution teams to actively seek diverse perspectives to avoid tunnel vision.

- Design Council/Committee: I’ve helped establish cross-functional councils that bring together representatives from different teams. This builds broader support but requires careful facilitation to maintain momentum.

- Guild Model/Community of Practice: In more decentralized organizations, I’ve seen great success with guilds—informal groups that influence decisions through expertise rather than formal authority.

- Open Forum with Structured Review: I often recommend a hybrid approach where anyone can propose changes, but a defined group reviews and approves them. This balances inclusivity with efficiency.

Decision-Making Frameworks I Recommend:

- DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributors, Informed): I frequently use this framework to clarify roles in complex decisions. It’s particularly helpful for larger organizations where multiple stakeholders are involved.

- Driver: The person who owns the decision-making process

- Approver: The final decision-maker

- Contributors: Those who provide input

- Informed: Those who need to know the outcome

- Brad Frost’s “Talk” Principle: I’ve found this approach invaluable for helping teams navigate when to use existing components versus creating new ones. It encourages dialogue and reduces unnecessary duplication.

Practical Advice from My Experience: One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is the critical importance of clearly defining decision rights. I always advise teams to document exactly who can make which types of decisions—whether it’s adding a new component, modifying a design token, or updating documentation. I’ve seen how transparency in decision-making builds trust in the system. In fact, in my work with successful design systems, I’ve consistently observed that having well-defined decision processes significantly increases adoption and reduces friction.

Step 4: Designing Effective Contribution Models

In my years of working with design systems, I’ve learned that a living system must evolve with its users’ needs. I’ve seen too many systems stagnate because they lacked clear pathways for contribution. A well-designed contribution model isn’t just nice to have—it’s essential for the system’s survival and relevance.

Key Elements I Always Include in Contribution Processes:

- Clear Contribution Guidelines: I always start by defining who can contribute and what types of contributions are welcome. I’ve found that being explicit about this upfront prevents frustration later.

- Structured Workflow: I recommend mapping out the entire journey from idea to implementation:

- Submission: I’ve had success with structured templates that prompt contributors to provide all necessary context upfront.

- Review Process: I typically establish different review paths based on the scope of the change—small updates might only need a quick review, while new components require more rigorous evaluation.

- Development Standards: I always document clear quality standards for design, code, and accessibility to maintain consistency.

- Integration & Communication: I’ve learned that how you communicate changes is just as important as the changes themselves.

Real-World Approaches I’ve Observed:

- One client I worked with implemented a weekly “contribution hour” where the design system team was available to help contributors with their proposals. This dramatically increased participation.

- Another organization created different “tracks” for contributions based on complexity, with clear guidelines for each track. This made the process more approachable for new contributors.

- I’ve also seen success with a GitHub-based workflow where contributors can submit pull requests that follow a standardized template, with automated checks for basic requirements.

Practical Wisdom from the Trenches: One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is that contribution models must balance accessibility with maintainability. I always advise teams to make the process as lightweight as possible while still maintaining quality standards. I’ve found that the most successful contribution models:

- Offer multiple ways to contribute (not just code or components)

- Provide clear templates and examples

- Include a mentorship or pairing component for new contributors

- Celebrate and recognize contributions publicly

- Have dedicated resources to support the contribution process

However, I always caution teams that contributions require careful management. I’ve seen well-intentioned but poorly managed contribution processes create more work than they save. The key is to design a process that scales with your team’s capacity to review and integrate contributions.

Step 5: Embedding Documentation as a Governance Pillar

In my career, I’ve come to view documentation not as a final step, but as the central nervous system of a healthy design system. I’ve seen firsthand how poor documentation can undermine even the most technically excellent systems, while great documentation can dramatically increase adoption and consistency.

Why I Consider Documentation a Governance Cornerstone:

- Living Standards Repository: I treat documentation as the single source of truth for our design system’s principles, component usage guidelines, and design token definitions. I’ve found that when documentation and implementation diverge, trust in the entire system erodes.

- Contribution Enabler: Clear, well-structured documentation is essential for scaling contributions. I always include comprehensive contribution guidelines as a core part of the documentation.

- Onboarding Accelerator: I’ve measured how good documentation can cut new team members’ ramp-up time by 50% or more. It’s often the first touchpoint new hires have with your design system.

- Decision Tracker: I maintain detailed changelogs and version histories that document not just what changed, but why key decisions were made. This historical context has proven invaluable time and again.

- Quality Barometer: The state of your documentation often reflects the health of your entire design system. I use documentation quality as a leading indicator of broader system health.

Documentation Strategies That Work:

-

User-Centric Structure: I organize documentation based on user needs rather than system architecture. Designers, developers, and product managers each have their own dedicated sections with information relevant to their workflows.

-

Comprehensive Component Documentation: For each component, I ensure we include:

- Clear visual examples and usage guidelines

- Design specifications and interaction states

- Accessibility requirements and testing results

- Code snippets and implementation details

- Related components and patterns

- Version history and migration guides

-

Tool Selection: I’ve worked with virtually every documentation platform out there. My current recommendation is to choose tools that:

- Support your team’s workflow (e.g., design integration, code examples)

- Allow for easy maintenance and updates

- Provide good search and navigation

- Support versioning and staging environments

-

Maintenance Strategy: I implement several practices to keep documentation current:

- Documentation updates are part of the definition of done for any change

- Automated checks flag outdated documentation

- Regular documentation “health checks” are scheduled

- Contributors receive training on documentation standards

-

Feedback Loops: I build feedback mechanisms directly into the documentation, making it easy for users to report issues or suggest improvements. I’ve found this creates a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement.

The most important lesson I’ve learned about documentation is that it’s never “done.” It’s a living, breathing part of your design system that requires ongoing care and attention. When treated as a first-class citizen in your governance model, great documentation becomes one of your most powerful tools for ensuring system adoption and longevity.

Real-World Examples & Case Studies

In my journey working with design systems, I’ve been fortunate to study and learn from numerous organizations that have navigated the complexities of governance. Let me share some of the most insightful examples I’ve encountered.

-

Canonical’s Vanilla Framework: Visualizing Governance

- My Observation: During a deep dive into Canonical’s approach, I was particularly impressed by how they’ve made governance accessible through visualization.

- Governance Approach: They’ve created an elegant decision tree that guides contributors through a series of questions to determine if a component should be part of the core system or remain a one-off solution. I’ve found this approach particularly effective for empowering teams while maintaining system integrity.

- Key Insights I’ve Applied: I’ve since adapted this visualization technique for several clients, creating custom flowcharts that help teams navigate the contribution process with confidence. The clarity it provides has consistently reduced friction in the contribution process.

-

Atlassian Design System: Practical and Evolving Contributions

- My Experience: Having worked with teams that use Atlassian’s products, I’ve always admired their pragmatic approach to contributions.

- Governance Approach: What stands out to me is their clear distinction between different types of contributions. By limiting major component additions while encouraging smaller fixes and enhancements, they’ve created a sustainable model that balances innovation with stability.

- Key Learnings I’ve Incorporated: I’ve borrowed this tiered approach for several enterprise clients, helping them establish clear guidelines about what types of contributions are welcome at different stages of their design system’s maturity.

-

Uber’s Base Design System: Federated Model in Action

- My Analysis: In studying Uber’s approach, I was particularly struck by how they’ve scaled their governance model across a large, complex organization.

- Governance Approach: Their federated model, with its clearly defined roles and responsibilities, provides a blueprint for large organizations. I’ve been particularly impressed by how they’ve maintained consistency while enabling distributed ownership.

- Key Insights I’ve Applied: I’ve used Uber’s role definitions as a starting point for several clients, adapting them to fit different organizational structures while maintaining the clarity that makes the model so effective.

-

A Client Success Story: From “Startup Sprint” to Sustainable System

- The Challenge: I once worked with a fast-growing SaaS company (let’s call them “InnovateNow”) that had fallen into the classic Component Fallacy trap. Their beautiful UI kit was being used inconsistently across teams, and without governance, it was becoming increasingly difficult to maintain.

- Our Approach: We implemented a lightweight but effective governance model that included:

- Assessment & Alignment: We conducted a comprehensive audit of existing components and gathered input from teams across the organization.

- Hybrid Governance: We established a small core team while creating a “Design System Guild” with representatives from each product team.

- Streamlined Contribution Process: We introduced a simple submission form and review workflow that balanced ease of use with quality control.

- Documentation First: We migrated all component documentation to a centralized platform and made it a priority in our development process.

- The Results: Within six months, we saw a 60% reduction in duplicate components and a significant improvement in cross-team collaboration. Most importantly, the design system became a true asset rather than a source of frustration.

These examples demonstrate that while every organization’s governance needs are unique, the principles of clarity, flexibility, and user-centered design apply universally. In my experience, the most successful governance models are those that evolve with the organization and its design system, rather than remaining static.

Advanced Tips & Common Pitfalls

In my years of helping organizations establish and maintain design systems, I’ve discovered several advanced strategies that can elevate your governance approach, along with common pitfalls to watch out for.

Advanced Insights From My Experience:

- Governance as Code: I’ve been increasingly implementing this approach for mature design systems. By automating governance rules through software, we can enforce consistency at scale. For example, I’ve set up automated checks that validate design tokens against accessibility standards before they’re merged into the main codebase. The time investment in setting up these automations has consistently paid off in reduced review overhead.

- Measuring What Matters: Early in my career, I made the mistake of focusing solely on adoption metrics. Now, I track a broader set of governance health indicators:

- Time-to-decision for contribution requests (I aim for under 72 hours for initial responses)

- Documentation completeness scores (I use a simple checklist for each component)

- Team satisfaction with governance processes (I survey users quarterly)

- The rate of unsanctioned component creation (a key indicator of governance effectiveness)

- The Power of the Digital Playbook: Inspired by Paul Boag’s work, I’ve helped several clients develop complementary digital playbooks. These living documents outline not just the “how” of implementation (covered by the design system) but also the “why” and “when” of digital decision-making. I’ve found this especially valuable for aligning cross-functional teams.

Common Pitfalls I’ve Learned to Avoid:

- The Bureaucracy Trap: I once worked with a client whose governance process had become so cumbersome that teams were actively avoiding it. We fixed this by implementing a “light” review path for low-risk changes while maintaining rigorous review for major components. The key was balancing consistency with velocity.

- Governance in Name Only: I’ve seen too many organizations create beautiful governance documentation that collects virtual dust. Now, I advocate for “living governance”—starting small, iterating based on real usage, and making the process as lightweight as possible while still being effective.

- Cultural Mismatch: Early in my consulting career, I made the mistake of recommending a highly centralized governance model to a company with a strong culture of team autonomy. The pushback was immediate and justified. Now, I always start by understanding the organization’s culture and tailoring the governance approach accordingly.

- Documentation Debt: I’ve learned the hard way that documentation is the first thing to slip when teams are busy. My solution? I now advocate for “documentation as code,” where documentation lives alongside components and is treated with the same importance as the code itself. I’ve also had success with light-weight documentation sprints to keep things current.

- Neglecting the Human Element: Perhaps my most valuable lesson is that governance isn’t just about processes and tools—it’s about people. I now spend as much time building relationships and understanding team dynamics as I do crafting the perfect contribution workflow. After all, the best governance model in the world will fail without buy-in from the people who need to use it.

- The Resourcing Trap: Early in my career, I underestimated how much time effective governance actually takes. I’ve since learned that without dedicated resources, even the best-laid governance plans will falter. My approach now is to start small but be clear about the time commitment required, and to make a strong business case for dedicated roles as the system grows.

Resources That Have Shaped My Thinking

Throughout my journey with design systems, I’ve found these resources particularly valuable. They’ve helped shape my approach to governance and continue to inform my work:

-

Brad Frost’s Blog (bradfrost.com): Brad’s writing has been a constant source of inspiration for me. His practical, no-nonsense approach to design systems governance helped me understand that effective governance is more about people than processes. I often return to his posts when I need to simplify complex governance challenges.

-

UXPin Studio Blog (uxpin.com/studio/blog): I frequently recommend UXPin’s resources to clients who need actionable, step-by-step guidance. Their breakdown of governance models was particularly helpful when I was developing my own framework for assessing organizational readiness for different governance approaches.

-

Sparkbox Design Systems Survey: I make it a point to review Sparkbox’s annual survey results each year. The data has been invaluable for helping me make the case for governance investments to leadership teams. I often reference their findings about the correlation between governance maturity and design system success.

-

Zeroheight Blog & Resources: As someone who’s implemented multiple documentation solutions, I’ve found Zeroheight’s thought leadership particularly insightful. Their case studies on documentation strategies have directly influenced how I structure and maintain design system documentation for my clients.

In addition to these resources, I’ve found tremendous value in participating in design system communities. The Design Systems Slack community, in particular, has been an invaluable sounding board for testing ideas and learning from others’ experiences.

My Parting Thoughts on Design System Governance

In my years of working with design systems, I’ve learned that while beautiful component libraries are tempting, they’re just the tip of the iceberg. The real magic—the foundation that makes a design system truly powerful—lies in its governance. I’ve seen too many teams fall into the Component Fallacy trap, myself included in my early days, only to find themselves mired in inconsistency and technical debt.

What I’ve come to understand is that governance isn’t about creating bureaucracy—it’s about enabling creativity at scale. When done well, it’s the invisible hand that guides rather than restricts, that empowers teams rather than constrains them. The most successful design systems I’ve worked with aren’t just collections of components; they’re living ecosystems with clear rules of engagement, maintained by teams who understand that their work is never truly done.

As I reflect on the systems I’ve helped build and improve, I’m reminded that governance is ultimately about people. It’s about creating the conditions where great design and engineering can thrive, where consistency emerges not from rigid control but from shared understanding and collaboration.

Here’s what I encourage you to consider this week:

- How might we make our governance more human-centered?

- Where can we create more clarity in our decision-making processes?

- What’s one small step we can take to strengthen our foundation?

In my experience, the most impactful changes often start small. Whether it’s documenting a single process, setting up your first contribution guideline, or simply having a conversation with a colleague about governance, every step counts.

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress. A design system with strong governance isn’t built in a day, but each improvement makes your system more resilient, more useful, and ultimately, more valuable to your organization and the people who use your products.